The Death of Animation? Why on earth is this the title I've chosen to pick for this topic of discussion? After all, hasn't Disney fully rebounded since the disastrous post-Renaissance years and hasn't Nickelodeon and Cartoon Network shown signs of life after years of ineptitude? Isn't animation at a high point that is only comparable to it's inception years in the 1930's or more recently in the times of the most magical films ever such as Aladdin, Toy Story, The Land Before Time, etc.?

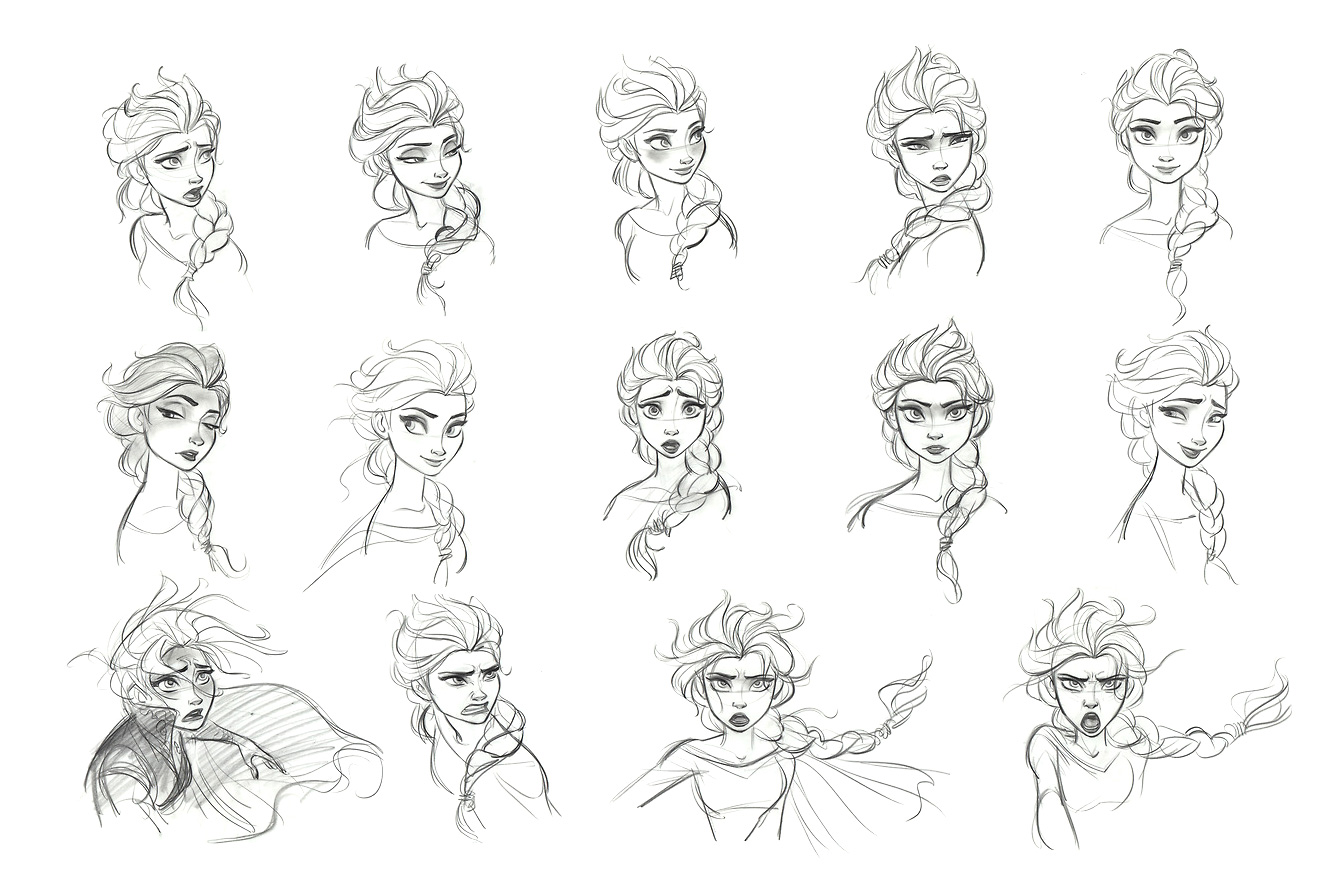

No. No it's not. Now this may be coming from someone who grew up in undoubtedly the most beloved age of Animation and may sound as though I am a crusty 21 year old curmudgeon who knew what "Real Art" was. But the more I think about it, the more I offer my time to exploring what animation is showing us as a collective audience, with a few stark exceptions from both television (Steven Universe, Star vs The Forces of Evil, Adventure Time) and in film (Frozen, Inside Out), animation is in no better shape now than it was when I was ten and starting to drift from the medium I have come to love since I was born. While I still find animation from my childhood as engaging and delightful as when I was a boy, I cannot seem to get into most of what has come about since I have reached what many call, "The Childhood Barrier". Why is this? Why can I not find much joy out of things from my childhood as I should be able to from this new age? Is the content really as bad as I have led you all to believing, or is there something I'm missing? In this essay, I will be trying to come to a conclusion on this question that has been bugging me for months now and will also be commenting and enlightening those who know little to nothing about the medium on exactly what the medium is, how much of our culture is built on it, and even how little they know was given to us through what was considered then as simple experiments.

What is Animation?

Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. It is said that most animated films rely on the phi phenomenon, which is basically optical illusions that allow our eyes to see things that move that are actually stationary. The art of allowing pictures to flow to one another to create a sequence has been around since the earliest days of art, though it has not been thoroughly explored until the 19th and 20th centuries.

Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. It is said that most animated films rely on the phi phenomenon, which is basically optical illusions that allow our eyes to see things that move that are actually stationary. The art of allowing pictures to flow to one another to create a sequence has been around since the earliest days of art, though it has not been thoroughly explored until the 19th and 20th centuries. Animation has rapidly evolved since it's initial phases. Multiple forms of animation have surfaced over the decades, from what is considered by many to be "Traditional Animation", which utilizes pencils and paper, to more modern forms including "Stop Motion Animation" and "Computer Generated Imagery" or CGI for short. These many forms of animation were used throughout films since the initial days of films, to create illusions and spectacles only visible to the imagination (such as vast armies of soldiers, horrific transformations, etc.). Nowadays, there are commercials, video games, television shows, internet shows, and movies based on the medium that could only have been a pipe dream but one hundred years ago.

While animation has ranged from the simple and basic (such as the famous animation of the bouncing ball), to the idea of a beautiful ball gown appearing out of thin air around a hopeless maiden, the art form owes it's existence to all forms of art from the most basic cave men paintings to the best that Van Gogh and Da Vinci could muster. Nothing in animation happens easily, nor does it happen overnight. Imagine if you will, a school art project you have poured your heart and soul into since it was announced. It takes you about a week or two to perfect the image and even then you can sometimes second guess yourself and try to make improvements. Now, imagine pouring your heart and soul into about 26 of those, which only equates to about a second of film. The sheer insanity that would bring out of even the most crazy of perfectionists would definitely not surprise me.

The Dawn of the Medium

Animation had been a fascinating concept to people for centuries prior to the 1900's. Many inventions were created to better help people experience the illusions of movement aside from the standard hypnotic spirals. These ranged from the practical kaleidoscope, to the more robust zoetrope, and even the simple flip book. The limitations of these objects are obvious, but without these innovations in the medium, the art form we all subscribe to this day would not exist.

The true dawn of Animation as a viable source of entertainment began with the invention of the "cinematographe" in 1894 by the very founders of motion pictures, Auguste and Louis Lumiere. The cinematographe was a camera, projector, and printer in one that allowed moving pictures to be shown successively and successfully on screen for any audience to enjoy. This was expanded upon by a French schoolteacher named Charles-Emile Reynaud, Instead of photographing multiple images and playing them about in succession, Reynaud drew the images onto the transparent slip that filled right in, allowing for the classic optical illusions to be formed.

Many are considered the fathers and founders of animation, and while men such as Chuck Jones and Walt Disney are praised as the innovators and masters of the art form, the true pioneer of American Animation was J. Stuart Blackton, who created the first American Animated Short Film called Humorous Phases of Funny Faces, which ran for about 3 minutes and consisted only of doodles on a chalkboard of a clown playing with a hat and a dog jumping through a hoop, drawn with chalk. While not nearly as long or as captivating as what is made today, it was still an important milestone in the art form.

By the 1910's, animated shorts had garnered the name that has stuck with them since then: cartoons. By then, animation was utilizes in many shorts and films made during the time. Such fans of the medium included the famous Charlie Chaplin and many of the original filmmakers, who utilized the art form to make their films better and more believable. But many were apprehensive to the idea of a film made entirely of animated films, and any hopes for the medium to achieve true enlightenment was put on hold with the advent of the First World War. That war in particular was a largely important thing in the lives of future animation legends. One man in particular was moved by what he saw serving as part of the Red Cross in France during the latest stages of the war that he became determined to break the boundaries animation had to offer. This same young man was transfixed by recollections of the stories of Peter Pan, Snow White, the Little Mermaid, Cinderella, and Jack and the Beanstalk and himself even saw one of the first motion picture versions of the Brothers Grimm Fairie Tales as a teenager in 1916. This man was named Walter Elias Disney.

A Man Named Walt

To say that Walt Disney was the sole reason for the successful rise of animation would be a bit of an overstatement. In fact, Walt stopped animating on his own cartoons in the 1930's. But as a business mastermind and a technological genius, few could compare to him. Walt found little to no success in his films early on, finding whatever work in the medium he could after the war. He attempted to form his own business in Kansas City called "Laugh-O-Grams", but when he could not turn enough of a profit, declared bankruptcy and moved out to California with only pocket change to his name and reunited with his brother and lifelong business partner Roy Disney. There, in Burbank California, they formed the Disney Brothers Studio. They would find success in animation the same way most did, combining it with live filmed action starring a little girl by the name of Virginia Davis. The "Alice Comedies", which were loosely based off of Lewis Carroll's famous "Alice in Wonderland", were a financial success for Walt and Roy, allowing the two to begin to hire animators full time and sign their first contracts as filmmakers.

By the time the "Alice Comedies" faded into obscurity, Walt had already found his next star character. With a cavalcade of animators whom would eventually go on to create their own characters (such as Ub Iwerks and the future Looney Tunes mastermind Friz Freleng), he envisioned the creation of a character by the name of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. As Oswald began to absorb the success Felix the Cat had previously had, Disney was starting to become relevant. But as with most visionaries, the corporate slimeballs tried to bring them down. This time, in the form of a man named Charles Mintz (which I think the Up spin on him being a villain is hilarious), who had tricked Walt into signing away his rights to Oswald and even attempted to buy off Walt's animators. While many, including Freleng, were indeed bought off, Walt and Ub Iwerks left their contract and moved onto their next endeavor. No longer would Walt create cartoons simply to make cartoons. He would create animated films that would always push the very boundaries of the medium. This would begin with the cartoon short "Steamboat Willie", his first animated film with synchronized sound and the official debut of a mouse named Mickey. The cartoon's success found for Disney a longtime character to build around, and not just a cavalcade of characters. From this point forward, Walt would pioneer many of the things that now are believed to be commonplace in animation, including colorized cartoons, special effects, and sweeping camera techniques that even now are replicated. But we'll cover Walt Disney a bit more later down the line.

Fleischer's Challenge

Walt Disney wasn't the only animator breaking new grounds in the early days of the medium. One of his earliest competitors was the artistic genius, Max Fleischer. Fleischer is the first animator to combine both music and sound into cartoons, and even synchronized them with perfection in the cartoon "My Old Kentucky Home". But despite his success as a pioneer, Fleischer received little of the adulation and praise Walt received for doing the same. Figuring this was due to not having a "franchise" character, he began to experiment with cultivating a new face of his studio. These faces would range from Koko the Clown to the first true female animated icon, Betty Boop. Whereas most female characters in animation were basically male characters with either longer eyelashes or a bow on top (Minnie Mouse), Betty was the first truly realized animated female, though even she lacked the realism that would be needed to turn cartoons into feature length films. This was due to the hard work and studying of one of Fleischer's best men, Grim Natwick, who would play a vital role in the history of animation, just not with Fleischer or Paramount...

Boop's success as a character began to show audiences that Disney did not yet have a strangle hold on the medium. But it wasn't until he would obtain the rights to a comic strip character by the name of Popeye the Sailor, would he upend Disney and obtain temporary dominance in the markets. Signed on by Paramount, Fleischer would become the primary drawing card for a studio on the brink of total collapse due to the Great Depression. But the studio's shortsighted views of "money only" type deals would hinder Fleischer's ability to challenge Disney, who would again retake the medium for the remainder of the 1930's, until another animation team would achieve dominance in the field.

The Looniest Bunch

But if you were looking to the one studio that achieved things we thought unattainable in the past, I would point to the wiles of the masters of slapstick and comedy at Warner Brothers. Led by a ragtag group of former Disney Employees such as Friz Freleng and of course the likes of Tex Avery and eventually Chuck Jones, these animators would try to replicate the success that Disney was having, but would push cartoons into territory where people thought previously impossible. Despite a slow start centered around a character that oddly resembled Mickey Mouse (and it's not even subtle), Warner Brothers would find immense success with the character of Porky Pig, who would be later joined by the likes of Elmer Fudd, Daffy Duck, Yosemite Sam, Foghorn Leghorn, Sylvester and Tweety, Wile-E-Coyote, and many others to become the Looney Toons (a play on the name of a cartoon series Disney was utilizing at the time). But the Looney Toons found immortality with the creation of one rabbit in particular. Bugs Bunny has since become a true American icon, forever immortalizing his creators and Warner Brothers, standing as their icon the same way Mickey stands for Disney.

But if you were looking to the one studio that achieved things we thought unattainable in the past, I would point to the wiles of the masters of slapstick and comedy at Warner Brothers. Led by a ragtag group of former Disney Employees such as Friz Freleng and of course the likes of Tex Avery and eventually Chuck Jones, these animators would try to replicate the success that Disney was having, but would push cartoons into territory where people thought previously impossible. Despite a slow start centered around a character that oddly resembled Mickey Mouse (and it's not even subtle), Warner Brothers would find immense success with the character of Porky Pig, who would be later joined by the likes of Elmer Fudd, Daffy Duck, Yosemite Sam, Foghorn Leghorn, Sylvester and Tweety, Wile-E-Coyote, and many others to become the Looney Toons (a play on the name of a cartoon series Disney was utilizing at the time). But the Looney Toons found immortality with the creation of one rabbit in particular. Bugs Bunny has since become a true American icon, forever immortalizing his creators and Warner Brothers, standing as their icon the same way Mickey stands for Disney. Unlike Disney Cartoons, which were seen as purely child's entertainment, the Looney Tunes and the Merrie Melodies series were able to appeal to all ages, with jokes ranging from dynamite shoved down a guys pants all the way to highly adult oriented humor, breaking the fourth wall repeatedly, among other things. Bugs Bunny and his friends were able to reach us in ways no one had before and every single animator looks to them as the masters of physical comedy in the same ways they look to classic comedians for their delivery sketches and whatnot. Once they dethroned Disney in the cartoon department, they held on with a firm grip and would ultimately do battle with another slapstick pioneer who would emerge in the 1940's and almost steal their thunder completely. Nevertheless, virtually every comedian owes their deliveries, their timing, and even develop their senses of humor from the likes of a bunch of anthropomorphic animals wanting no more than to torment each other...

Expanding a Universe

Animation was growing into a more appealing form of entertainment with each and every cartoon that was made, be it mediocre or more memorable than the movie they were attached to. But while animators like Fleischer were cash strapped and forced to comply with studio regulations, and while the Friz Flemengs of the world all enjoyed their success they found in the physical comedy market, one studio in particular was determined with each passing year to surpass them all. Pioneered by his success with "Steamboat Willie" in 1928, Walt Disney began to build his mighty animation empire on the back of Mickey Mouse and continued to expand the very foundations of the art form he'd come to love. By 1929, all of Disney's cartoons utilized synchronized soundtracks. By 1932, by a stroke of fiscal shortsightedness by Paramount, Walt had achieved a monopoly on colorized animated cartoons.

Animation was growing into a more appealing form of entertainment with each and every cartoon that was made, be it mediocre or more memorable than the movie they were attached to. But while animators like Fleischer were cash strapped and forced to comply with studio regulations, and while the Friz Flemengs of the world all enjoyed their success they found in the physical comedy market, one studio in particular was determined with each passing year to surpass them all. Pioneered by his success with "Steamboat Willie" in 1928, Walt Disney began to build his mighty animation empire on the back of Mickey Mouse and continued to expand the very foundations of the art form he'd come to love. By 1929, all of Disney's cartoons utilized synchronized soundtracks. By 1932, by a stroke of fiscal shortsightedness by Paramount, Walt had achieved a monopoly on colorized animated cartoons. The idea of colorizing a cartoon was brought to Walt's attention by Herbert Kalmus, the inventor of a colorization technique called Technicolor, who hoped to reintroduce color into feature length films after the Great Depression caused many cutbacks in studios. Seeing the vast opportunity in line for him, Walt signed an exclusive contract through 1935 with Technicolor, making him it's only customer for over four years. Max Fleischer had attempted to get a similar if not equal deal for Paramount, but Paramount had turned him down due to having strict monetary restrictions. In 1932, "Flowers and Trees" was released in Disney's "Silly Symphonies" series, and turned the fledgling series into a smash success, earning an Academy Award for Walt with his pioneering use of color in his cartoons. With the success of his cartoon, the Academy would then institute a permanent award for an animated short.

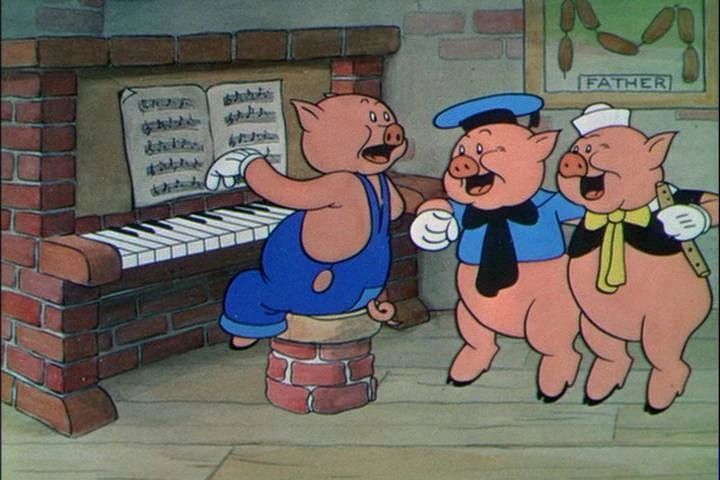

But Walt wasn't done at just colorizing his cartoons. He, like the animators at Warner Bros., knew that animation would never survive past the Depression without allowing his cartoons to be looked at with more human eyes than just the eyes of children looking for a laugh. He sought to add personality to his characters and saw music as a vital cog for his future cartoons. While the Looney Toons and Popeye cartoons would all have very distinct themes and melodies, Disney knew that in order for him to diversify his entertainment capabilities, he would have to make each cartoon as unique as possible. This would lead to the creation to the perfect foil to Mickey Mouse in his best friend, the hot tempered and difficult to understand Donald Duck. But it would also lead Disney's animators to find immense success with a classic retelling of the fairy tale, "The Three Little Pigs".

The cartoon was a pioneer in two regards. Firstly, it was a pioneer in character animation. While the Looney Toons would perfect this craft in the future, Disney had found this vital in the creation of the four characters that appeared in this short. Each of the pigs had it's own personality, along with the Wolf, which had an entirely sneaky and conniving personality of his own. Walt and his animators finally learned an important lesson: audiences found themselves remembering cartoons more if they could remember the characters.

Secondly, the cartoon was a stunning success in determining if music was needed to develop his pictures. Hiring songwriter Frank Churchill and eventually the likes of Larry Morey and Ned Washington would prove vital to his successes down the road, but it was Churchill who composed the song "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf" which was so popular, that it was donned the theme song of the Great Depression. Walt took full advantage of it and made it one of the most popular songs of the decade. Once again, the audiences responded to the songs and the music in the picture just as much as they did the characters. This success would further convince Walt of two things: that he and his artists were more capable then he had ever imagined, and that his studio would not survive on just making 7-9 minute cartoons...

A 90 Minute Cartoon?

Though Max Fleischer and Walt Disney despised each other for many years as rivals, the one thing they could agree on was that the animation medium would not survive on what the studios paid them for their cartoons. On average, animation studios and branches were paid roughly 1/10 of the gross receipt of a motion picture they were attached to. So, if a film would earn about $500,000 at the box office, the studio was paid $50,000 for their share. The problem was, that animated shorts were rising in costs each and every year. In fact, "The Three Little Pigs" cost the Disney studio about $35,000 to make.

Though Max Fleischer and Walt Disney despised each other for many years as rivals, the one thing they could agree on was that the animation medium would not survive on what the studios paid them for their cartoons. On average, animation studios and branches were paid roughly 1/10 of the gross receipt of a motion picture they were attached to. So, if a film would earn about $500,000 at the box office, the studio was paid $50,000 for their share. The problem was, that animated shorts were rising in costs each and every year. In fact, "The Three Little Pigs" cost the Disney studio about $35,000 to make. A few animated films had been attempted across the globe, but none had even been attempted in Hollywood. Fleischer experimented with elongated shorts of Popeye the Sailor, one of which included a retelling of the story of Aladdin and his Wonderful Lamp. As a two reel cartoon, it was trying to tell a full and complete story in a span of 22 minutes. It was one in a trilogy of cartoons called the "Popeye Color Specials", and were actually acclaimed and successful upon release. But these were still not garnering enough money for the studio to truly stand on. Fleischer still held out hope that Paramount would allow him to create a feature length animated film.

But once again, his rival had the edge on him. Having signed a new contract with RKO Pictures, Walt Disney was basically given freedom to do as he pleased so long as he earned profits. But even RKO was taken aback by Walt's declaration of his desires to make a cartoon feature that could be billed as its own picture. The world was apprehensive to the idea of a feature length cartoon, creating such excuses as "The bright colors would hurt your eyes" and "The audience would get tired of seeing 90 minutes of cartoonish gags". Proving he was one step ahead of everyone, Walt had been secretly planning to create an animated film for years. but was waiting for his artists to stabilize themselves in the art form. Most were recently unemployed men and women who needed jobs and needed proper education in the world of art. Very few were ready for the high demands a full length animated film would demand.

Walt was in need of inspiring his animators, doing everything in his power to recruit the best in the business to his side. This included the likes of European artists such as Gustaff Tengren and Albert Hurter and even one of Fleischer's top animators, Grim Natwick, whom had perfected the animation of the female in Betty Boop. Gathering his full strength, Walt finally decided on the film he wanted to make first. It would be a retelling of one of the first films he saw in theaters as a young man, and a fairy tale he had grown up with: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

But the making of what the media would prematurely dub "Disney's Folly" would be a much more difficult battle than either Walt or his brother Roy could anticipate. The film was estimated to take 2 years to make and would cost roughly $500,000 dollars. Though the Bank of America (the financial bank of the Motion Picture industry) clutched at it's collective heart, it was still a manageable budget and they approved for the massive loan. As many of his artists were still immature when it came to animation, Walt realized that it would take a great deal of experimentation to complete his motion picture. He refined and sculpted the story down to its barest essentials, due to the extreme problems his artists would face animating the human figures in the movie, such as Snow White and the Evil Queen. The Prince in particular was so difficult to manage, that he was scaled back to only appearing in two whole scenes in the film. But one story meeting in particular would set the standard for which all animated films would be judged. As a story man illustrated to his fellow animators the frightened Snow White's flight through the haunted forest and her plunge into a river some 20 or so feet, one of the animators chimed in and asked quite sincerely, "Wouldn't a fall like that kill her?" With that lone question, they knew they were on the right track.

The heart of the animation team on Snow White was headed by four main animators: Fred Moore, Vladimir (Bill) Tytla, Norm Ferguson, and Art Babbit, who would become the masters of Disney Animation until they passed along the torch to their successors, all whom are famously dubbed "The Nine Old Men", but we'll talk about them later. Moore was one of the studio's best character designers and was essential in the creation of the Seven Dwarfs. Art Babbit, who is imfamously known for his later actions towards the studio, was a master animator who took on the difficult task of animating the Wicked Queen. But these men could not have done as well without the "Nine Old Men", all of whom played anything from minor to major roles in the film technically.

Churchill was once again hired to write the songs for the film. However, his task this time around was to make the songs in the film not only be as memorable as his previous success, but also have the songs not stall the progress of the movie. Some twenty five songs were said to have been written for the film, but only eight made it into the final film. Although the success rate for a song was only 32%, the ultimate results would revolutionize the way all film and stage musicals would be told. Songs would no longer be used as entertaining time wasting moments in shows. Instead, they would be vital to the overall integrity of the film and would carry the studio for many decades to come.

While Walt began to steer his pet project in the right direction, he needed to let his animators have the time and practice animating and building the medium towards what he demanded. He began to create projects entirely to help develop Snow White. These would include:

"Babes in the Woods", a Silly Symphony that would help the animators animate to a centralized plot.

"The Goddess of Spring", a Silly Symphony to help the animators learn how to animate humans more properly and how to convey darker imagery and scenes into their pictures.

...among others. One short in particular, "The Old Mill" was utilized to test a new invention fabricated by Ub Iwerks (and later improved upon by William Garity), borrowing from the early designs of Lotte Reiniger, which she used to create her animated film, The Adventures of Prince Achmed, which was made and released in Argentina in 1926. Iwerks invention utilized four separate layers of artwork, each meant to depict a different part of character, background and foreground, all shot with camera aimed vertically. Each layer of artwork would move as the camera needed it to, to better demonstrate depth and realism for each and every major drawing that needed such depth. The Multiplane Camera would prove essential for many years to come for the studio, and would finally see it's last use by Disney in 1989.

As with most artistic endeavors, there is a price to be paid, be it time or fortune. And in the case of Walt Disney's precious animated gamble, it was most certainly the budget. By summer 1937, the studio was completely out of money. All of their borrowed money (which had doubled to $1,000,000) was being sunk into the film, and in order to meet their Christmas 1937 deadline, they would need another $500,000 to complete the film. The bankers were apprehensive to the idea and refused to sink another dime into the project until they got to see where all of it was going. Fearing they would reject it due to it's incompletion, Disney initially refused, until the leader of the bank, Joe Rosenberg insisted on seeing it. Walt relented to show Rosenberg an unfinished version of the film. Because so much of the film had yet to be properly colored and some scenes were even still in storyboards (which were crudely yet passably drawn sketches of what a scene was supposed to depict). Being the master of storytelling that he was, Walt tried desperately to sell the idea of Snow White to Mr. Rosenberg, who simply sat beside him and nodded. As the duo parted later that day, it is said that Rosenberg told Walt in these finite words: "That film is going to make you a hat full of money". Within days. Walt's $500,000 dollar loan was approved and the film was finished on time.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs premiered at the Carthay Circle Theatre on December 21, 1937. The premiere was attended by virtually the entirety of Hollywood's most elite company, including the likes of Clark Gable, Charlie Chaplin, Shirley Temple, and Judy Garland. Despite his fears of the audience not reacting the way he hoped, the audience watched and treated the film as though it were a live action story. They laughed at all the humorous moments, gasped at all the frightening moments, and shed plenty of tears when they all feared Snow White had in fact died at the hands of the Wicked Queen. But when the Prince's kiss woke her from the spell, the audience erupted in applause. It was a day Walt knew he would never forget.

Walt Disney's so called "Folly" would become the top grosser of it's time, earning over $8,000,000 dollars worldwide and garnering widespread critical praise wherever it played. With the profits he'd earned, Walt put the money back into the business and began construction on a massive new studio for his animators to work in, which is still the headquarters for the company to this day. Come awards season, Walt would receive a special Academy Award with one large statue and seven smaller statues attached. The film also received two more Academy Award nominations for Best Song and Best Score (a trend that Disney would have for quite some time).

The enormous success of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs would change the landscape for motion pictures and animation forever. Max Fleischer was immediately allowed to move on to animating his own animated film, Gulliver's Travels, which was also a success at the box office. But conflicts soon arose from Paramount, which would result in the studio buying out Fleischer's studio, firing him, and renaming the studio Famous Studio. To compete with the immense success of Disney's, MGM would greenlight arguably their most famous film, The Wizard of Oz, as a musically enhanced family picture. Warner Bros. would tease the studio with their own mockeries of Disney films, such as "Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs", a highly controversial and racist cartoon. But it was Walt himself who was changed the most. Now, with his artists more confident and able, he was able to begin work on the next few animated films of his. But in the bubble of Hollywood, you could not see the gathering storm clouds lurking around the world, which would turn all of the success animation had been garnering upside down by the start of World War II...

No comments:

Post a Comment