The Rise of Hanna-Barbera and Saturday Morning Cartoons

Not everything about this era was a downside, as much as I made it seem in the last page of this essay. While the were ousted from MGM at the end of the 1950's, William Hanna and Joseph Barbera were able to create their own cartoon company, Hanna-Barbera. But with the decline of interest in cartoons in Hollywood and on cinemas (aside from Disney's feature length films), they needed a new medium to appeal to audiences. Then it hit them. What was being deemed the downfall of the motion picture industry as they spoke? Television. While mavericks like Walt Disney took advantage of television to garner greater profits, most of the filmmakers and animators snubbed television. But no one could deny how wonderful it was and how accessible it was in comparison to often hard to get to cinemas.

While it would take many years for cartoons to catch onto the mainstream, there was always a safe and hallowed place for cartoons to blossom and garner eager children: Saturday Mornings. While airing children's programming on Saturday mornings was no new idea (as it had been going on since the early days of television), it wasn't until the late 1950's and early 1960's that those time slots on many major channels would be filled by cartoon content from various companies (including DePatie-Freleng Enterprises (Pink Panther), Total Television (Underdog), and Jay Ward Productions (Rocky and Bullwinkle and George of the Jungle). The styles of most of these cartoons reflected the popularity of UPA's cartoons in the 1950's. This is most visible in Jay Ward cartoons, including Rocky and Bullwinkle, which would reuse many backgrounds and animation scenes in order to accommodate for their often minuscule budgets.

But the most popular cartoons of this age were being animated by Hanna-Barbera, Starting with a particular blue dog with a southern drawl named Huckleberry Hound, they would create a menagerie of characters that would become fond memories our parents tried to teach us when we were watching our cartoons in the 90's or watching Boomerang in the 2000's. These characters included the likes of Snagglepuss, Quick Draw McGraw and his alter ego El Kabong, and Ricochet Rabbit. But the most popular of these Saturday morning cartoons in the early 1960's was a certain character who was "smarter than the average bear". Yogi Bear, named for the baseball player Yogi Berra, was a resident of fictional Jellystone Park, who would harass picnickers trying to swipe their goodies instead of foraging for his own food like normal bears. Roping in his protege Booboo and sometimes even the park ranger, he would go to extraordinary lengths just to have a few human snacks and have many adventures along the way. Despite Yogi's high popularity, he was just one of the many popular franchises Hanna-Barbera would create in the 1960's.

Past and Future

Even with the success of Saturday morning cartoons, the idea of animation being a serious lineup option for the prime time lineup was still far-fetched an idea to the mainstream television audience. While it is believed that a Disney-esque show (such as Mickey Mouse Club) would be passable, the idea of a Hanna-Barbera show being on at the same time as news shows and games shows was ludicrous an idea to many. If they were to garner the respect they wanted and no longer be considered a "kids only" company, they knew they would have to model their show after one of the most popular shows of the time. Selecting "The Honeymooners" as the show they wanted to emulate, and chose to set the show in the Stone Age, taking many infamous liberties as they did. The result was the most popular prime time animated show in history (a record it would hold until the premiere of "The Simpsons" in the 1980's). "The Flintstones" appealed to the mainstream audiences in ways only a few shows could. It followed the daily life of couple Fred Flintstone and his wife Wilma, along with the lives of Fred's best friend Barney Rubble and his wife Betty. They had jobs and set up many of the basic stereotypical sitcom formulas, such as forgetting an anniversary, among other things.

Even with the success of Saturday morning cartoons, the idea of animation being a serious lineup option for the prime time lineup was still far-fetched an idea to the mainstream television audience. While it is believed that a Disney-esque show (such as Mickey Mouse Club) would be passable, the idea of a Hanna-Barbera show being on at the same time as news shows and games shows was ludicrous an idea to many. If they were to garner the respect they wanted and no longer be considered a "kids only" company, they knew they would have to model their show after one of the most popular shows of the time. Selecting "The Honeymooners" as the show they wanted to emulate, and chose to set the show in the Stone Age, taking many infamous liberties as they did. The result was the most popular prime time animated show in history (a record it would hold until the premiere of "The Simpsons" in the 1980's). "The Flintstones" appealed to the mainstream audiences in ways only a few shows could. It followed the daily life of couple Fred Flintstone and his wife Wilma, along with the lives of Fred's best friend Barney Rubble and his wife Betty. They had jobs and set up many of the basic stereotypical sitcom formulas, such as forgetting an anniversary, among other things.

The smash success of "The Flintstones" increased the demand for more cartoons in prime time slots. But what could the studio create to top their biggest success? Why, the exact opposite idea of course. Instead of the Stone Age, why not have a show take place in the future? And instead of having a more "Honeymooners" approach, why not slip back into more childish ideas? Well, the reaction to the show was about as well as you'd think. It wasn't as though "The Jetsons" was a bad show, but the fact that Hanna-Barbera immediately retreated back towards it's "kids only" company level made things so much worse for the company. Following the futuristic (yet somehow dated) exploits of George Jetson and his family, the show covered much of the same ground as their predecessor show, with a futuristic edge. It wasn't the success Hanna-Barbera hoped it would be, but the show still garnered success and acclaim for the studio in a time when their content was beginning to show signs of recession.

Fall from grace...

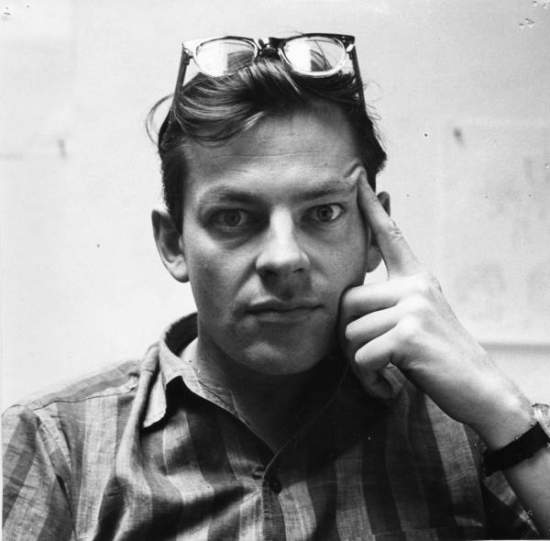

But not all cartoons released in this era were on television, and not all of them were successful as Hanna-Barbera's short had been. After their shortsighted dismissal of Hanna and Barbera had crippled their ability to make animated shows, alongside their need to obtain extra funds for their better movies, MGM saw the need to revamp Tom and Jerry for a new age. But with their creators long gone, they needed a new animation team to work on their shows. They selected Gene Deitch and Rembrandt Studios in Prague to animate the cartoons, which is yet another bad decision made by management. While the shorts were well liked by children, Gene Deitch has gone on the record as saying he was ill prepared for animating for this show (having only worked on UPA stylized cartoons), and the shorts he created were panned by critics. Deitch (who has also been known for saying he was never a fan of Tom and Jerry), still believed that he could have animated better shorts if given the opportunity, but MGM did not grant him another chance.

But not all cartoons released in this era were on television, and not all of them were successful as Hanna-Barbera's short had been. After their shortsighted dismissal of Hanna and Barbera had crippled their ability to make animated shows, alongside their need to obtain extra funds for their better movies, MGM saw the need to revamp Tom and Jerry for a new age. But with their creators long gone, they needed a new animation team to work on their shows. They selected Gene Deitch and Rembrandt Studios in Prague to animate the cartoons, which is yet another bad decision made by management. While the shorts were well liked by children, Gene Deitch has gone on the record as saying he was ill prepared for animating for this show (having only worked on UPA stylized cartoons), and the shorts he created were panned by critics. Deitch (who has also been known for saying he was never a fan of Tom and Jerry), still believed that he could have animated better shorts if given the opportunity, but MGM did not grant him another chance. Tom and Jerry was then passed along to Chuck Jones, who had been recently fired by Warner Bros. and was in the need to animate something with his new animation studio, Sib Tower 12 Productions. However, these shorts were also lukewarmly received. Not because the animation quality was poor, but because Chuck Jones was (despite being a master animator) not versed in the way of Tom and Jerry, his cartoons came off with more of a Looney Toons appeal, with more of the traditional Chuck Jones "breaking the 4th wall" jokes and focused more on the reactions to the pain than the pain itself. As a result, Tom and Jerry continued to fade past it's time and was ultimately cancelled in 1967.

The Xerox Process

Following the immense failure of Sleeping Beauty in 1959, Walt Disney Productions capsized much of it's animation department, including the entire Ink and Paint department, which had given all of the previous films their remarkable beauty and style unique to them. As a result, Walt and his remaining animators sought the need to find a way to produce his animated films in a similar way to his older films, but with more attention given to the cost. If the studio suffered another cataclysmic failure, the animation department would be forced to shut it's doors. The solution was found by the aging animator Ub Iwerks, who had been a Special Processes artist at the studio since his return to the studio in the 1930's. Iwerks invented a Xerox camera that could directly transfer animators drawings onto a cel without the need of paintwork and inking. This would cut the cost of their films in half and would allow the animator's distinct vision to be seen by audiences. Despite seeing this as a great way to keep animation moving along, Walt was concerned with it's appeal to his audiences and the cost of colored ink. The experimental animated film that utilized the Xerox process for the first time was One Hundred and One Dalmatians. Considering that dalmatian dogs were almost always just black and white, this was an excellent choice for their first film.

Following the immense failure of Sleeping Beauty in 1959, Walt Disney Productions capsized much of it's animation department, including the entire Ink and Paint department, which had given all of the previous films their remarkable beauty and style unique to them. As a result, Walt and his remaining animators sought the need to find a way to produce his animated films in a similar way to his older films, but with more attention given to the cost. If the studio suffered another cataclysmic failure, the animation department would be forced to shut it's doors. The solution was found by the aging animator Ub Iwerks, who had been a Special Processes artist at the studio since his return to the studio in the 1930's. Iwerks invented a Xerox camera that could directly transfer animators drawings onto a cel without the need of paintwork and inking. This would cut the cost of their films in half and would allow the animator's distinct vision to be seen by audiences. Despite seeing this as a great way to keep animation moving along, Walt was concerned with it's appeal to his audiences and the cost of colored ink. The experimental animated film that utilized the Xerox process for the first time was One Hundred and One Dalmatians. Considering that dalmatian dogs were almost always just black and white, this was an excellent choice for their first film. The animation in the film is very choppy and has been criticized by animation critics for decades, but it would keep the studio in business, so it was sort of a double edged sword. But like the best Disney films, the appeal of the characters was enough to draw in audiences, particularly with the highly popular villain Cruella De Vil. One Hundred and One Dalmatians was successful in it's domestic release and would become one of the most popular films the studio would release, ultimately grossing over $200 million dollars at the domestic box office all time.

The great success of the film can also be attributed to the studio's top story man, Bill Peet. Peet had been an animator at the studio since the 1930's and had helped establish some of the most acclaimed scenes in Disney history, including the Mad Hatter Tea Party. By 1959, he was the only story man in the studio and was more than eager to take on the challenges that were in front of him. Peet would be placed in unofficial control of their next film, The Sword in the Stone, to much less successful results. Peet's word was law until the weak reception to Stone, a comical look at the King Arthur stories, to which Walt would take complete control of his animation studio again to tackle their next film, The Jungle Book.

Sheer Holiday Perfection...

By the start of the decade, the comic strips of Charles M. Schulz were becoming immensely popular. Starring the unlucky and unliked Charlie Brown, his beagle Snoopy, and cast of characters dubbed "The Peanuts", these comic strips were some of the highlights of someone's divulge into a newspaper reading. The success was noticed by producer Lee Mendelson, who wanted to create a documentary on the success of the strip. But no major animation studio was interested in the documentary. Only Coca-Cola was interested in the production, and it was only if the Peanuts documentary was transformed into a Christmas special. And, they also had a strict due date of December 9th, 1965. With only six months to draw up a framework for the special, Schulz and Mendelson were now in desperate need to make this special stand out in comparison to other specials of the time. He started by wondering what the true meaning of the holiday was. With his deeply religious background, Schulz was determined to give his special a religious message that would stand out amongst all of the commercialism that surrounded the holiday. Animation for the short was worked on by animator Bill Melendez (a previous Disney and Warner Bros. employee), who was almost flabbergasted at the six month due date. The budget went over by almost $35,000. But the animation on A Charlie Brown Christmas was finished within ten days of it's premiere.

By the start of the decade, the comic strips of Charles M. Schulz were becoming immensely popular. Starring the unlucky and unliked Charlie Brown, his beagle Snoopy, and cast of characters dubbed "The Peanuts", these comic strips were some of the highlights of someone's divulge into a newspaper reading. The success was noticed by producer Lee Mendelson, who wanted to create a documentary on the success of the strip. But no major animation studio was interested in the documentary. Only Coca-Cola was interested in the production, and it was only if the Peanuts documentary was transformed into a Christmas special. And, they also had a strict due date of December 9th, 1965. With only six months to draw up a framework for the special, Schulz and Mendelson were now in desperate need to make this special stand out in comparison to other specials of the time. He started by wondering what the true meaning of the holiday was. With his deeply religious background, Schulz was determined to give his special a religious message that would stand out amongst all of the commercialism that surrounded the holiday. Animation for the short was worked on by animator Bill Melendez (a previous Disney and Warner Bros. employee), who was almost flabbergasted at the six month due date. The budget went over by almost $35,000. But the animation on A Charlie Brown Christmas was finished within ten days of it's premiere. Like another animated milestone released almost thirty years earlier, the short was foredoomed to failure by many in the media. But the simplistic nature of the animation, the realism of the characters, and the deep and thought provoking message appealed to people in a way no Christmas special had before. Very few Christmas specials in 1965 would dare talk about religion, and this show directly read from the bible in an effort to show everyone the true meaning of the holiday. The show has since garnered widespread critical acclaim and is one of the most popular Christmas specials ever made. The success of A Charlie Brown Christmas prompted many more Peanuts Holiday Specials and many other Christmas specials released during this era.

Fun Fact: With A Charlie Brown Christmas came the abrupt end to the popular trend of aluminum Christmas trees, as the show mocked their commercialism and how they had completely ignored the true meaning of the holiday...

The Marvel Super Heroes

One thing I have yet to talk about is the appeal of Comic Books on the medium of animation. I have avoided talking about them because I could go off on an entire tangent about their appeal and growing success and even had about a third of Page I dedicated to them. I omitted comic books, along with children's books like the Seuss books, but it would be very wrong of me to not cover the roots of the future successes of super hero cartoons. Fueled by their quick rise to success with comic series such as X-Men, The Avengers, Spider Man, and so forth, Marvel Studios and Grantray Lawrence Animation combined their efforts to create a Looney Toons show to show off their multitude of comic book characters, including Captain America, Thor, Iron Man, and the Hulk. They often followed comic book storylines and kept to the cheesy comic book motifs and cliches. While it was very subpar by modern standards, the show appealed to boys and was the first exposure to these heroes we got if we couldn't get into comic books.

One thing I have yet to talk about is the appeal of Comic Books on the medium of animation. I have avoided talking about them because I could go off on an entire tangent about their appeal and growing success and even had about a third of Page I dedicated to them. I omitted comic books, along with children's books like the Seuss books, but it would be very wrong of me to not cover the roots of the future successes of super hero cartoons. Fueled by their quick rise to success with comic series such as X-Men, The Avengers, Spider Man, and so forth, Marvel Studios and Grantray Lawrence Animation combined their efforts to create a Looney Toons show to show off their multitude of comic book characters, including Captain America, Thor, Iron Man, and the Hulk. They often followed comic book storylines and kept to the cheesy comic book motifs and cliches. While it was very subpar by modern standards, the show appealed to boys and was the first exposure to these heroes we got if we couldn't get into comic books. Rumbly in my Tumbly...

Ever since the 1930's, Walt Disney had been trying to acquire film rights to a popular book series written by A.A. Milne. The reason he wanted the film rights was because of how much his daughters had loved the series. A.A. Milne's storybooks were based on the "adventures" his son Christopher Robin had with his stuffed bear named Winnie the Pooh. Winnie the Pooh lived in the fictional Hundred Acre Wood alongside many other stuffed animals in Christopher Robin's nursery, including the timid Piglet, the gloomy donkey Eeyore, and the constantly bouncing tiger named Tigger. Pooh was a bear of very little brain, but the one thing he could always think of was filling his gluttonous stomach with honey. Milne's books were immensely popular in Great Britain, but had not been fully integrated into American society at that point. Walt hoped to change that when he finally acquired the film rights to a few of Milne's books.

Ever since the 1930's, Walt Disney had been trying to acquire film rights to a popular book series written by A.A. Milne. The reason he wanted the film rights was because of how much his daughters had loved the series. A.A. Milne's storybooks were based on the "adventures" his son Christopher Robin had with his stuffed bear named Winnie the Pooh. Winnie the Pooh lived in the fictional Hundred Acre Wood alongside many other stuffed animals in Christopher Robin's nursery, including the timid Piglet, the gloomy donkey Eeyore, and the constantly bouncing tiger named Tigger. Pooh was a bear of very little brain, but the one thing he could always think of was filling his gluttonous stomach with honey. Milne's books were immensely popular in Great Britain, but had not been fully integrated into American society at that point. Walt hoped to change that when he finally acquired the film rights to a few of Milne's books. In order to properly introduce Winnie the Pooh and his friends to American audiences, Walt decided to break up the originally full length animated film into separated segments, beginning with Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree, which premiered in 1966 to widespread popularity. Since his debut, Pooh has become one of the studio's most popular characters, allowing the franchise to be marketed throughout all sorts of mediums, including movies, television shows, video games, merchandise, and more. This first featurette would ultimately be joined by Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day (Which won the Academy Award), and Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too in becoming one full feature length animated film in 1977 as The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh.

A Death in the Family...

Walt Disney Productions was one of the most successful studios in Hollywood by 1966. They held sway over television, motion pictures, theme parks, and all sorts of merchandise that people bought daily. Walt and his brother Roy had built the studio from the bottom up until it was one of the supreme leaders in the entertainment industry. They had helped lead animation into it's Golden Age, pioneered technical achievements in filmmaking, and were the proud owners of the biggest tourist attraction in California. But even with all of this success, Walt was not satisfied. Secretly buying up massive tracts of land in central Florida, Walt revealed to the world his intention on building something much larger than Disneyland, but an entire Disney World, which would be the biggest undertaking in the company's history.

Walt Disney Productions was one of the most successful studios in Hollywood by 1966. They held sway over television, motion pictures, theme parks, and all sorts of merchandise that people bought daily. Walt and his brother Roy had built the studio from the bottom up until it was one of the supreme leaders in the entertainment industry. They had helped lead animation into it's Golden Age, pioneered technical achievements in filmmaking, and were the proud owners of the biggest tourist attraction in California. But even with all of this success, Walt was not satisfied. Secretly buying up massive tracts of land in central Florida, Walt revealed to the world his intention on building something much larger than Disneyland, but an entire Disney World, which would be the biggest undertaking in the company's history. However, not all of the things happening around Walt Disney was positive. He went into the hospital in 1966 to fix an old injury he had suffered while playing polo back in the 1930's. But while going through his X-rays, Walt was told he had a tumor on his left lung. Having the lung removed in November, Walt was given the timeline of six months to two years to live. Walt was determined to complete his last stages of work on all of his dream projects, including fixing and fine tuning what would become the very last animated film he personally supervised.

Bill Peet was given the green light to develop a story based on Rudyard Kipling's magnum opus, The Jungle Book, prior to the release of The Sword in the Stone in 1963. But the latter's failure forced Walt to take drastic measures to oversee the production of the film himself. When Peet presented his treatment for the film, he was shocked to see Walt had rejected it. When the two argued over how to make the film, Peet left the studio, never to return. Walt was determined to turn Kipling's dark and moody set piece into a breezy, laid back, Sparknotes retelling of the story with only the most minute similarities to the book. Walt made sure his animators focused entirely on personality animation, even going as far as to have best friends Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston animate roughly 65% of the film themselves. Walt's decisions also included hiring personal friend George Sanders and popular icons Phil Harris and Louie Prima to portray characters in his films. He also revamped the music, hiring studio musicians Robert and Richard Sherman to write the songs, effectively eliminating the songs written by Terry Gilkyson, with the exception of the most famous song from the film, "The Bare Necessities".

But before the film could be completed, Walt returned to the hospital in December 1966, and would never come out, dying on December 15th, 1966. The company was devastated at the loss of Walt, as was the country. Without Walt, many felt the company would capsize. But determined to see through his last goals and dreams, Roy Disney moved ahead with the plans to create Walt Disney World while the animators worked tirelessly to complete The Jungle Book, which finally premiered in theaters in October 1967. Marketed as "The Last Disney Film", the film was an immense success at the box office, garnering more money than any animated film had ever done previously and prompted the Nine Old Men to begin cultivating the next generation of animators to succeed them.

The Origins of Anime

To say that the success of Disney's animation department is far reaching is an understatement. The immense success felt by the studio with Snow White was influential on all part of animation, and not just domesticated animation. Animation had been a thing in Japan since prior to WWII, and their customary big wide eyes and short bursts of animated action were showing signs of birth as early as the 1940's. But the American population did not become aware of the rising Japanese artform until the 1960's, This was due to the rise in popularity of a new form of illustrated story, the manga. The manga utilized Japan's unique style to tell various fables and stories in the same vein as comic books here in America. But whereas comic books often pandered down to whichever demographic they were aiming for, manga could range from graphically violent or comedically childish in a single volume.

To say that the success of Disney's animation department is far reaching is an understatement. The immense success felt by the studio with Snow White was influential on all part of animation, and not just domesticated animation. Animation had been a thing in Japan since prior to WWII, and their customary big wide eyes and short bursts of animated action were showing signs of birth as early as the 1940's. But the American population did not become aware of the rising Japanese artform until the 1960's, This was due to the rise in popularity of a new form of illustrated story, the manga. The manga utilized Japan's unique style to tell various fables and stories in the same vein as comic books here in America. But whereas comic books often pandered down to whichever demographic they were aiming for, manga could range from graphically violent or comedically childish in a single volume. The success of the anime in both Japan and America can be attributed to the career of Osamu Tezuka, who is considered by many in the industry to be the Japanese equivalent to Walt Disney. While he'd worked on multiple stories and ideas, Tezuka had two projects he is best known for. The first was Kimba the White Lion, an anime following the story of an orphaned white lion cub trying to keep peace between the humans and the animals of his kingdom (which bears some subtle similarities to a later big budget animated film, but nothing drastic). The other was Astro Boy, a sort of superhero retelling of Pinocchio, where an inventor creates an android to replace his dead son. Both shows were successful enough to have American companies try and fail to create imitation copies, but neither would truly propel anime into mainstream America until the 1980's. But the seeds of the new art form had been planted. All it needed was another guiding hand...

Action for Children's Television (ACT) and the Dawn of the Dark Age

Television brought many unexpected (yet should have been anticipated) issues to the forefront. Most importantly, it brought his notion of fear among parents that television (a tool that they had used to keep children quiet on Saturday mornings), was now becoming too influential on children. Many parental focus groups arose out of this time and actually had a ton of power over the communication airwaves. These parents believed in censoring anything they did not deem appropriate on all aspects of television children could watch, including heavily censoring and banning multiple classic cartoons from the airwaves. Tom and Jerry saw no airtime without heavy censorship and the Looney Toons even cooperated with these parents by making less violent and more focused stories. It was no surprise that despite still retaining name popularity. Among things censored for children included the complete abolishment of commercials during the time children most watched television. While these are in practice good ideas, the practice with which these groups went about was generally unyielding and contributed dangerously to a new trend that animation is still trying to escape from.

Television brought many unexpected (yet should have been anticipated) issues to the forefront. Most importantly, it brought his notion of fear among parents that television (a tool that they had used to keep children quiet on Saturday mornings), was now becoming too influential on children. Many parental focus groups arose out of this time and actually had a ton of power over the communication airwaves. These parents believed in censoring anything they did not deem appropriate on all aspects of television children could watch, including heavily censoring and banning multiple classic cartoons from the airwaves. Tom and Jerry saw no airtime without heavy censorship and the Looney Toons even cooperated with these parents by making less violent and more focused stories. It was no surprise that despite still retaining name popularity. Among things censored for children included the complete abolishment of commercials during the time children most watched television. While these are in practice good ideas, the practice with which these groups went about was generally unyielding and contributed dangerously to a new trend that animation is still trying to escape from. "Animation is just for kids."

"Why would I want to watch that kid stuff?"

"It was fun when I was a kid, but..."

These quotes became very telling of the next twenty or so years of the medium. No one in the media took animation seriously anymore. The decline in interest intensified over the years into very few animated products becoming successful, causing many networks and studios to completely abandon animation or relocate it overseas to countries such as Japan and South Korea. Animation would remain very stagnant over the next several years and would take a combination beyond anyone's comprehension to rescue the medium. Because while many frown upon the 2000's as a bad time for animation, the 1970's were a bad time for animation all across the board...

Scooby Dooby Doo!

Most people look endearingly on the success of Hanna-Barbera's various "Scooby Doo" series. I don't. Despite it's immense success, Scooby Doo was one of the driving causes of the decline of animation in the 1970's. The plots of the show were simple and easily recyclable and allowed for animation to be just as easily recycled as it's stories. The characters were basic stereotypes (Velma was the nerd, Daphne was the DID, Fred was the leader, Shaggy was the coward, and Scooby was the dog), and would be the foundation for almost a dozen spinoffs and ripoffs over the next forty years.

While the spinoffs have ranged from mediocre to tolerable over the years, the ripoffs were by far the worst. In the 1970's alone, half of all of the content being animated in the decade was based off of this easy to recycle formula. These shows included: Josie and the Pussycats, Jabberjaw, The New Scooby Doo Mysteries, The Tom and Jerry Show (which was the first truly gut wrenching show), various Flintstones shows, among others. The primary suspect of these crimes was Hanna Barbera, who by the 1970's was almost as creatively bankrupt as possible and was facing the intense likelihood of bankruptcy, with no truly successful shows being made at the time. No one should truly look upon Scooby Doo with as much reverence as they do, because even though the original show was harmless, it jeopardized the medium into complete eradication...

The Magic is Missing...

However, whereas Hanna-Barbera had the excuses of ACT and creative bankruptcy to hamper them in this dark era, Disney did not have that luxury. Disney has often cited this era as their "Dark Age", with many animated films being made with every intention of having the magic of it's predecessors, but for some reason missing it. Disney created three animated films in the 1970's (Because 2/3 of the segments of The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh were made in the 1960's, I don't count it), and none of the films are looked upon with as much reverence as one would think.

However, whereas Hanna-Barbera had the excuses of ACT and creative bankruptcy to hamper them in this dark era, Disney did not have that luxury. Disney has often cited this era as their "Dark Age", with many animated films being made with every intention of having the magic of it's predecessors, but for some reason missing it. Disney created three animated films in the 1970's (Because 2/3 of the segments of The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh were made in the 1960's, I don't count it), and none of the films are looked upon with as much reverence as one would think. The first animated film, The Aristocats, follows the adventures of a family of well kept cats abandoned by their owner's greedy butler hoping to steal their future inheritance. With jazzy cats, gossiping geese, among other animals, the film was aimed directly at children, something that always dooms Disney when they follow through with that formula. Though the film was a success in 1970, it's less than stellar animation and easily childish story aren't enough for it to be viewed as a classic by many in the industry.

Robin Hood, on the other hand, has received great praise over the years by fans despite not being successful at the box office (with respect to the numbers grossed by it's predecessor and successor). The story follows the basic events of Robin Hood's life, told by anthropomorphic animals, including his robberies of Prince John and subsequent rivalries with him and the Sheriff of Nottingham and romance with Maid Marian. While the action is much better than The Aristocats and the story is much more suspenseful, the lack of depth and emotion in the story works against it and it, despite the best intentions, is again not strong enough to warrant success.

The Rescuers often gets lumped into the same category as The Aristocats, but I find much more flaws within this film than most others do. With the most simplistic take on the animation (including the odd choice of taking the white out of the two main mice's eyes), weak and flimsy villains, and a meandering plot cost this film in my mind to make it the worst Disney Film deemed "A Classic". However, The Rescuers is one of two films made by the studio in this era that was being used as training films. With many of the Nine Old Men retiring and passing away, they had begun a recruiting and training process with the Disney sponsored college, The California Institute of the Arts, or CalArts. Many of the names in these classes and programs would be filled with many of the most influential people in both animation and Hollywood overall, including John Musker and Ron Clements (The Little Mermaid, Aladdin, The Princess and the Frog), John Lassetter (Toy Story, Finding Nemo, Frozen), Tim Burton (Beetlejuice, The Nightmare Before Christmas, Edward Scissorhands), among others.

The Forgotten Gods

As with the rise of Saturday Morning Cartoons, not all things that occurred in this era were bad, but not all of it gets the attention it deserves. Specifically, two animators emerged around this time that do not get their due praise and respect. While their most prolific and successful work would be made in the next era, these two began to get their feet wet in this otherwise dreary era of animation. The first was Richard Williams, a British based Canadian who worked on many smaller term animated projects in the time, Willaims would direct the Oscar winning short, "A Christmas Carol" alongside "Raggedy Ann & Andy: A Musical Adventure". Despite his long list of works in this time, Williams spent much of his time working on what he considered to be his magnum opus, "The Thief and the Cobbler". Williams independently funded much of the film and kept it in and out of work for the bulk of nearly thirty years. He'd recorded screen giant Vincent Price to play his villain Zigzag in the 1960's but the film would be released shortly after Price's death in 1992.

As with the rise of Saturday Morning Cartoons, not all things that occurred in this era were bad, but not all of it gets the attention it deserves. Specifically, two animators emerged around this time that do not get their due praise and respect. While their most prolific and successful work would be made in the next era, these two began to get their feet wet in this otherwise dreary era of animation. The first was Richard Williams, a British based Canadian who worked on many smaller term animated projects in the time, Willaims would direct the Oscar winning short, "A Christmas Carol" alongside "Raggedy Ann & Andy: A Musical Adventure". Despite his long list of works in this time, Williams spent much of his time working on what he considered to be his magnum opus, "The Thief and the Cobbler". Williams independently funded much of the film and kept it in and out of work for the bulk of nearly thirty years. He'd recorded screen giant Vincent Price to play his villain Zigzag in the 1960's but the film would be released shortly after Price's death in 1992. Williams was best known for his very imaginative look on animation. This can be seen in his abstract scenes in The Thief and the Cobbler, alongside his interesting animation styles and ideals. He chose virtually any color design or style he felt would help give his animation meaning, being one of a few animators at the time that truly cared about what he was doing. His passion would cause Disney and Warner Bros. to recruit him for a top secret project they worked on in the 1980's, but more on that masterpiece later...

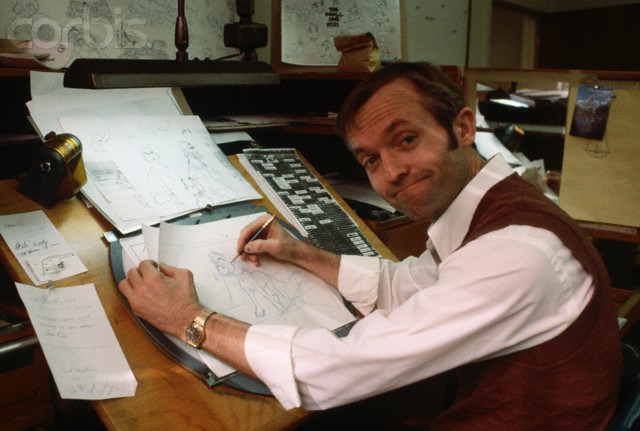

The other animator of this time was a longtime "Inbetweener" at Disney. Though he could trace his work back as far as Sleeping Beauty, Don Bluth slowly became a pioneering animator during the 1970's, and his deep knowledge of the art form was often looked to by management as a potential replacement for Walt. He was looked to by the younger animators as a sort of demi-god. Bluth's works for Disney included the likes of all films in the decade except for The Aristocats, Pete's Dragon, and the beloved short, "The Lost One". Bluth was also uncredited for storyboard work on later animated films for Disney, but this was because of his departure from the studio. Bluth had witnessed the decline of animation in Disney's eyes and detested how upper management viewed their library of work from years past as enough to keep the company afloat. When rumors surfaced about the department being closed down for good, Bluth and eleven other animators departed from the studio to make their own place in the business, setting back the release of The Fox and the Hound for Disney and leaving studio head Ron Miller and Disney betrayed.

The other animator of this time was a longtime "Inbetweener" at Disney. Though he could trace his work back as far as Sleeping Beauty, Don Bluth slowly became a pioneering animator during the 1970's, and his deep knowledge of the art form was often looked to by management as a potential replacement for Walt. He was looked to by the younger animators as a sort of demi-god. Bluth's works for Disney included the likes of all films in the decade except for The Aristocats, Pete's Dragon, and the beloved short, "The Lost One". Bluth was also uncredited for storyboard work on later animated films for Disney, but this was because of his departure from the studio. Bluth had witnessed the decline of animation in Disney's eyes and detested how upper management viewed their library of work from years past as enough to keep the company afloat. When rumors surfaced about the department being closed down for good, Bluth and eleven other animators departed from the studio to make their own place in the business, setting back the release of The Fox and the Hound for Disney and leaving studio head Ron Miller and Disney betrayed. Bluth's mastery of the animation would lead him to create some of the most beloved films of my childhood along with many who grew up in our time. His early independent works included the spectacularly animated The Secret of Nimh (a personal favorite of mine) and animation for the interactive laserdisc video game, Dragon's Lair. But his time in the sun would come eventually, once a legendary Hollywood director saw fit to stand beside him.

A New Medium

Despite the still successful advent of television, yet another medium was coming to life that would forever cripple television. Home Video. With the invention of both the VHS (Video Home System) and the Betamax in the 1970's, not only was recording live TV now possible, but now the idea began to spring about that maybe movies could be released to the general public for them to enjoy forever. Animated cartoons were now being released by numerous companies, including Warner Bros., MGM, Disney, and Paramount, to take advantage of the new medium. Movies were originally being held back, but by the early 1980's, even Disney had relented to releasing part of their animation library on home video, beginning with their package projects and a few of the "lesser" animated films, such as Alice in Wonderland and Dumbo. Most of the mainstream animated films made by Disney were being held back by management, out of fear that once these films were released on home video, they would forever lose the ability to make profit off of the re-releases of these animated films. The following films would be "Untouchable", until the 1984 creation of the Walt Disney Classics line:

Despite the still successful advent of television, yet another medium was coming to life that would forever cripple television. Home Video. With the invention of both the VHS (Video Home System) and the Betamax in the 1970's, not only was recording live TV now possible, but now the idea began to spring about that maybe movies could be released to the general public for them to enjoy forever. Animated cartoons were now being released by numerous companies, including Warner Bros., MGM, Disney, and Paramount, to take advantage of the new medium. Movies were originally being held back, but by the early 1980's, even Disney had relented to releasing part of their animation library on home video, beginning with their package projects and a few of the "lesser" animated films, such as Alice in Wonderland and Dumbo. Most of the mainstream animated films made by Disney were being held back by management, out of fear that once these films were released on home video, they would forever lose the ability to make profit off of the re-releases of these animated films. The following films would be "Untouchable", until the 1984 creation of the Walt Disney Classics line:Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio, Fantasia, Bambi, Cinderella, Peter Pan, Lady and the Tramp, Sleeping Beauty, One Hundred and One Dalmatians, The Sword in the Stone, The Jungle Book, The Aristocats, Robin Hood, The Rescuers, and The Fox and the Hound

One Last Hurrah

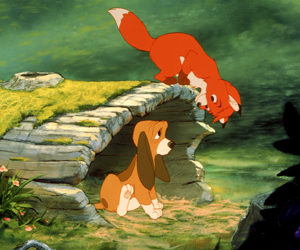

Despite the sudden departure of Don Bluth, the Disney Animation Department, headed by the remnants of the Nine Old Men, continued work on their next animated film, a fable about how a fox kit and a hound puppy became friends despite the prejudices of their society. While still maintaining much of the childishness of the previous decade, 1981's The Fox and the Hound would be one of the most beloved Disney films since The Jungle Book. It dealt with dark themes (such as prejudice, vengeance, and death), and treated it's audiences seriously rather than pander to them. While the film still missed part of the charm that older Disney films had, the film was beloved by critics and is still deemed a superior Disney film to all of it's contemporaries.

The film was the first to be truly animated by the next regime of animators. While some of the old guard remained (Art Stevens, Richard Rich, Joe Hale, Vance Gerry), most of the animators were being shown the path to the next golden age of animation. Names such as Don Hahn, Ed Gombert, Glen Keane, Mike Gabriel, John Musker, Ron Clements, Andreas Deja, and many others had something or other to do with the making of this film and would be the pioneers of Disney's greatest era. But the old guard and new guard would clash over how to tell these films and how to create them. This clash would continue throughout the 1980's, culminating in the film that nearly destroyed Disney Animation...but that's a tale for another page...

No comments:

Post a Comment